Dr. Denise Campagnolo is a Neurologist and EricsHouse Board member, and my collaborator on the EricsHouse research project to validate and explore the usefulness of our Grief Self-Assessment tool.

Denise recently shared an article with me, published in the JAMA Psychiatry Journal this past February, titled “Why Deaths of Despair Are Increasing in the US and Not Other Industrial Nations—Insights From Neuroscience and Anthropology”.

First, I have to say the label ‘Deaths of Despair’ really resonates with me. I have struggled to come up with a term that covers the range of losses we primarily focus on at EricsHouse (Suicide and Substance Abuse). ‘Deaths of Self-Harm’ is accurate but feels somewhat judgmental – there’s already far too much stigma attached to these losses. ‘Deaths of Despair’ honors the struggles our loved ones faced during their lives.

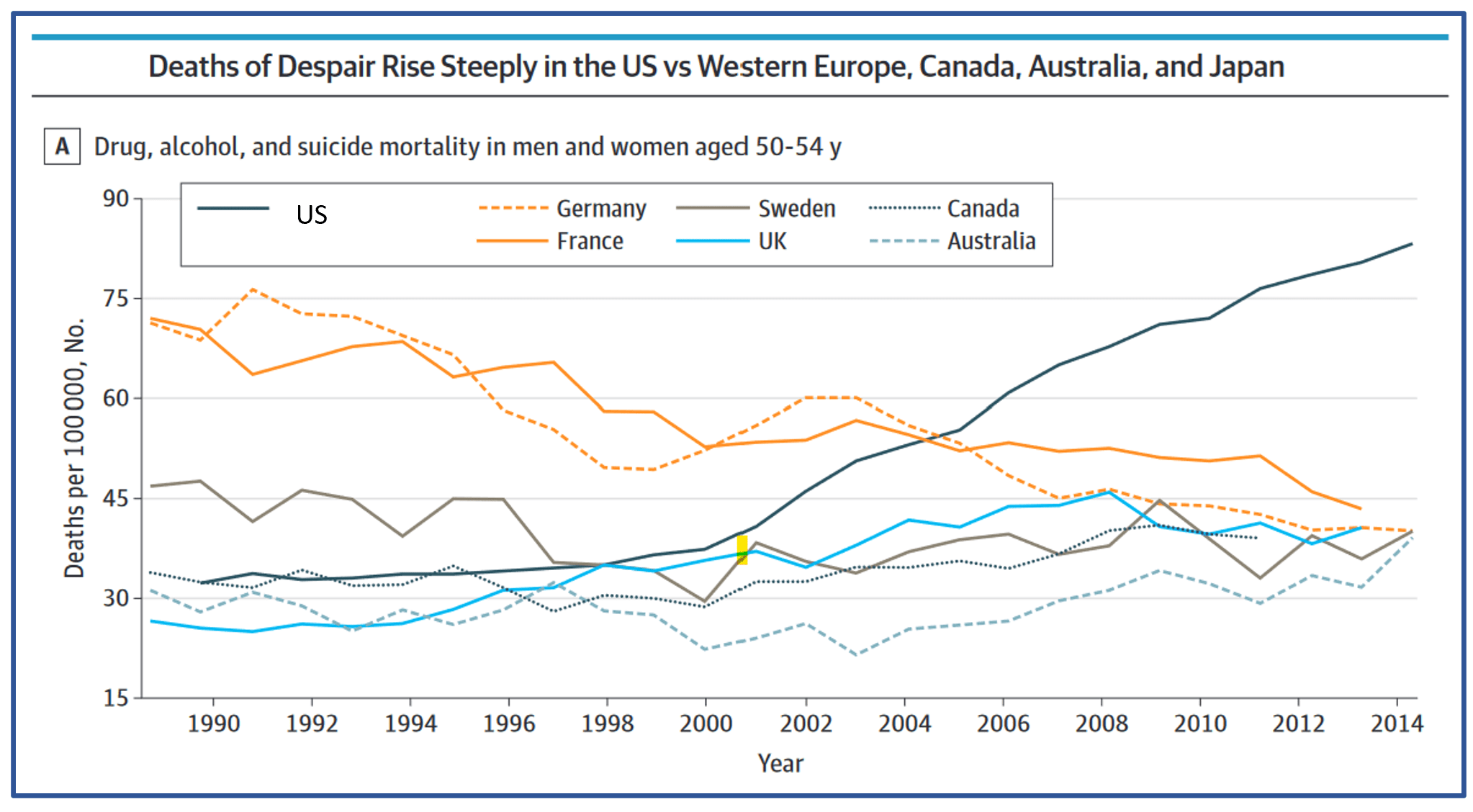

The article reviews a report by the US National Academy of Sciences documenting rising mortality for US adults, most steeply for White adults with a secondary education or less. The rise is largely attributable to deaths of despair (suicide and poisoning by alcohol and drugs) with strong contributions from the cardiovascular effects of rising obesity. . . The US National Academy of Sciences report notes that mortality is decreasing in a control group of 16 wealthy nations (including countries in Western Europe, Canada, Australia, and Japan) . . . ’ The rates of deaths of despair in the US are climbing dramatically, while those in the other 16 nations in the study are declining or flat (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Deaths of Despair Data

While the article rightly resists the urge to speculate on the causes of this crisis in the US beyond recommending studying the best practices of the other 16 nations, this data clearly begs the question: WHY? I feel compelled to speculate.

Perhaps it is related to the stigma attached to these deaths and to the despair faced by the victims in life. That stigma manifests in criminalization of addictions rather than effective recovery support, especially for those without the financial wherewithal to pay for it. It manifests in the persistent label of a loss to suicide as ‘committing’ suicide – just as one commits a crime . . . or commits a sin. Perhaps it is due in part to the limited availability of mental health support to those of limited means as well as the possible stigma for those seeking that support.

While I am reluctant to compare tragedies, since all of them play out at an individual level and it feels somewhat callous to evaluate them statistically, it is interesting to note the difference in levels of outrage over deaths by mass shootings and these deaths of despair. Based on the most recently available data in the US, deaths of despair outnumber deaths due to mass shootings by a factor of 3000. Compare the public outrage over mass shootings to that for the far greater number of deaths of despair.

We do need to study this to understand the root causes and address them. We need to learn from other nations with more effective mental health programs. We need to support and care for the victims while they are with us.

Recent Comments